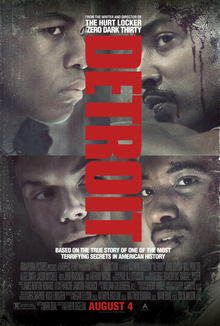

When you see Kathryn Bigelow's name, you instantly think of the onscreen combat movies that have garnered praise and critical acclaim from critics and fans alike. A master of blunt-force action, moral ambiguity, and onscreen combat, Bigelow has earned her stripes as a respected and sought-after director. So when her newest film, Detroit, was announced, you weren't sure what to expect. The previews left you guessing for the most part, but you know it had to do with a hot button topic today. One issue that should be alarming: this painful true event took place nearly fifty years ago.

Detroit takes place in 1967, during one of the largest race riots in United States History known as the 12th Street Riot. Amidst the chaos of the Detroit Rebellion, the city is under curfew and the Michigan National Guard are patrolling the streets along with the police force. The story centers around the Algiers Motel incident, where three young African American men were murdered. But the question remains: what really happened at the motel?

You see the beginning sparks of the riot after a raid on an all-black after-hours club celebrating the return of a solider from Vietnam. Because there is not a viable back exit, the arresting officers are forced to take the partygoers through the front door to waiting police vans. A crowd gathers and boos; bottles and epithets are thrown out as well. Like so many other parts of the country at the time already corroded by decades of fear and loathing on both sides of the racial divide, you can tell this city is a powder keg, and a spark isn't hard to find. For days, you see the riots play out as police do their best to contain and stop the violence; some taking it too far and costing lives.

As the streets burn, a motley crew of characters gather at the lively Algiers Motel: an aspiring R&B singer (Algee Smith) and his babyfaced hype man (Jacob Latimore); a weary veteran (Anthony Mackie); two freespirited white girls (Hannah Murray and Kaitlyn Dever) dipping their toes in the sexual revolution of the time. These strangers bond and flirt by the courtyard pool before moving inside. One guest (Straight Outta Compton's Jason Mitchell) pops off a starter pistol as a prank; the echoing shots provoke a rattled onslaught of law enforcement, including local officers Krauss (Will Poulter) and Demens (Jack Reynor), members of the National Guard, and night watchman Dismukes (John Boyega). What follows next during this second act of the film is historical record - albeit still a disputed one - even after several court cases, dozens of news articles, eyewitnesses over the last 50 years. (One would assume that Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal had done research to ground the script in known facts along with a dose of artistic license.) The second act of the film is tense and sometimes uncomfortable to watch as the police abuse their power in interrogating the hotel guests. Bigelow's focus comes back again and again to the ugly tug of power; whether that is attached to a badge or a bully's soapbox. You see small, but crucial, points in the film where this happens. A beat cop casually cupping a woman's backside as he "helps" her into a paddy wagon; the guardsman who smirks and asks Boyega for sugar when he offers fresh coffee; the pregnant pause before another carefully picks out the word Negro.

There is powerful acting in the leads such as Poulter; playing chilling enigma Officer Krauss. A rogue Boy Scout with a black space where his conscience should be. He kills as casually as a kid playing videogames - shooting a terrified looter in the back over a few groceries even after a colleague reminds him that they've been given explicit instructions to let low-level offenders go. Boyega is equally as good in a sometimes thankless role in both movies and real-life: the wary peacemaker who gets "Uncle Tom" spat at him from one side and a derogatory "boy" from the other. He's quietly magnetic, making it a wonder to watch his character think through each situation as far as where he lands.

Little screen time is wasted on motivation or backstory, but Bigelow's character all share one trait: a singular drive; a fixation that borders on mania. This is especially evident in Poulter's "I am the law" racist officer. Much of the movie lives in small impressionable moments, or in the prickly stillness before a scene explodes into brutal violence to make you cringe that this is happening. In a nation that seems to be as divided as it was in this film, I found that Detroit's aim was not to highlight a sort of institutionalized domestic terrorism or a political commentary on the relative matter of blue or black lives, but an effort to illuminate a singularly dark chapter in America's history - one that we are close to being in currently - and reminder of who truly loses when human beings, no matter your color, lose when we fail to take care of one another.

If you agree or disagree with my review, I understand. I would say to see this all-important film, which I consider to be a dark horse when Oscar season rolls around in a few months, and form your own opinion.

No comments:

Post a Comment